Dr Raj Rattan, dental director, discusses how to effectively reflect on clinical practice and its importance for risk managementIt was the Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who said, “No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man.” He was referring to the fact that change is constant. It could be said that no dentist carries out the same procedure twice because each clinical situation is different and that, by definition, each procedure adds to the experience of the clinician and therefore s/he is not the same dentist.

Clinical practice is informed by experience but only if it triggers reflective practice. As the American philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey put it, “We do not learn from experience…we learn from reflecting on experience.”

It requires self-awareness, critical analysis, synthesis and evaluation, and helps gain new insights into self and practice. It’s been likened to a spiritual process – connecting the inner-self with the outer-world.

There are two main types of reflection – reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action. The main difference is that the first takes place in real time. It happens during the procedure/event and the second takes place after the event.

1 Studies have shown that reflective practices are connected to outcomes, so the principle is beyond the theoretical. From a risk management perspective, both are of equal value but in very different ways.

Reflection-in-action provides opportunities for corrective actions and may prevent error and harm to the patient. It is usually intuitive.

Reflection-on-action is retrospective. It takes place sometime after the situation has occurred. It requires protected time and commitment. Schön emphasises its importance “to discover how our knowing-in-action may have contributed to an unexpected outcome”.

For this reason, reflective capacity is regarded as an essential element of professional competence. It integrates theory and practice from the outset. The risk management lessons derive from the ‘reflection corridor’ (figure 1, yellow highlighted zone) that encompasses the totality of the process over a timeline – where t1-t2 demarcates reflection-in-action from reflection-on-action at t3. Reflection-in-action should be a continuous process. It informs the procedure and vice-versa so that real time modifications and actions can be taken to ensure optimal outcomes for the patient.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Risk management lessons and the reflective corridor

Demonstrating reflection is essential for dentists appearing before the regulator. It demonstrates insight into the concerns under investigation and can impact the outcome. It is an integral part of our preparation in regulator cases to support members over and above the dentolegal aspects alone.

Activities to promote reflection are now being incorporated into undergraduate and postgraduate education across a variety of healthcare professions. For example, reflection is a requirement in the professional development portfolio during the foundation training year, and we encourage it after any unexpected incident or adverse outcome. It can also inform the content of a complaint response.

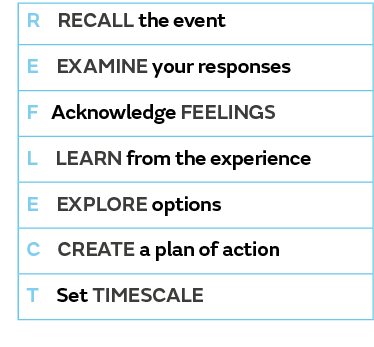

The REFLECT model, devised by Butcher, Whysall and Barksby, uses the mnemonic REFLECT to summarise the seven steps of reflection shown in Table 1.

2Table 1. The seven steps

Reflective practice promotes changes in our thinking and our approach to the delivery of clinical care, which is also influenced by legislation, regulation, new technologies and innovative treatment modalities.

The focus must be on feedback and actions – going beyond the simple descriptive narrative of what happened and why these actions must lead to change – to realise the full value of the process. By adopting this approach, risk management becomes an integral part of experiential learning and not an after-thought.

References

1 Schön, D.

The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, New York: Basic Books, Inc; 1983.

2 Barksby J, Butcher N, Whysall A. A new model of reflection for clinical practice,

Nursing Times 2015; 111:(34/35): 34–35.