Weight and see

Robert Caplin, senior teaching fellow, King’s College London, Dental Institute, looks at how properly weighing up the various factors in a decision can benefit both practitioner and patient Decisions, decisions…there is no doubt that we spend a lot of time making decisions, major and/or minor, that affect our lives, and of these many are around the area of purchasing goods or services.

In the competitive world that we live in, there is usually a wide choice and, while this is good, we will spend much time researching the advantages (benefits) and disadvantages (risks) of the various options before making a decision. We would like to think that the advice we are given is genuine and unbiased, although this is probably highly optimistic.

As dentists, we are providers of a service and our patients are the ‘buyers’ of the service that we provide for them. Can they be confident that the advice given is in their interests rather than the interest of the dentist?

The answer should be yes, because as a profession our relationship with those coming to us for care is defined and determined by certain standards set down by dentistry regulators around the world.

Difficult decision-making

What does this all mean for us practically? It means that we have to share with our patients the often difficult decisions that have to be made every day in dental practice to answer the who, how, why, when and where questions about interventions that arise when looking inside a patient’s mouth.

Dentistry is very stressful and contributing to this may be some incorrect assumptions, including that there is always a right, precise and perfect solution to a patient’s problems, and this solution must always be found.

I want to focus on this misunderstanding and promote the idea that there isn’t a probe that we can put on a particular tooth that will tell us what to do. Fill this one. Watch this one. Repair this filling. Put a post in that tooth. These are all decisions that are ultimately subjective and are, therefore, the reason for the variations that we see in care plans between different dentists, and even between the same dentist on different days and at different times.

There are several factors that contribute to these variations:

• Undergraduate/postgraduate training

• Time available

• Financial pressures

• Gender

• Age

• The environment that one is working in – be it general or private practice, hospital or academic.

1 All of these will influence, more or less, our choice or preference for treatment, even when discussing the options with the patient before us. As human beings, we are not as consistent and reliable as we would like to think. Like it or not, our decisions are going to vary.

Clearly, we have to have a consistent approach when examining a patient, even though we may not have consistent outcomes, and then need to take a holistic view of their problems. Any treatment option, be it active or passive, has to be in the best interests of the patient. The patient has to be better off following the treatment and the dentist, too, it is to be hoped, has to derive benefit from the interaction – satisfaction from a job well done, patient appreciation and, in some settings, financial reward, although this latter point is not relevant to obtaining consent from the patient.

Our clinical decisions, therefore, can have far-reaching consequences for the wellbeing of our patients and for ourselves. An acceptable care plan is one that can be justified to a third, independent party should the occasion arise. I want to take you on the path of critical thinking so that we can meet the requirements of our regulators by giving our patients all the options with their risks and benefits.

Let’s take a common clinical scenario:

This patient, a 70-year-old female, wanted the appearance of her upper right front tooth improved. The tooth is asymptomatic, vital and with no obvious periapical changes visible on the radiograph. The root canal in the upper right central incisor is patent and unobstructed. The gingival condition is acceptable.

Note the following: there is a vertical fracture line. The incisal edge of UR1 is not level with the incisal edge of UL1 (bruxing).The tooth has a range of colours.

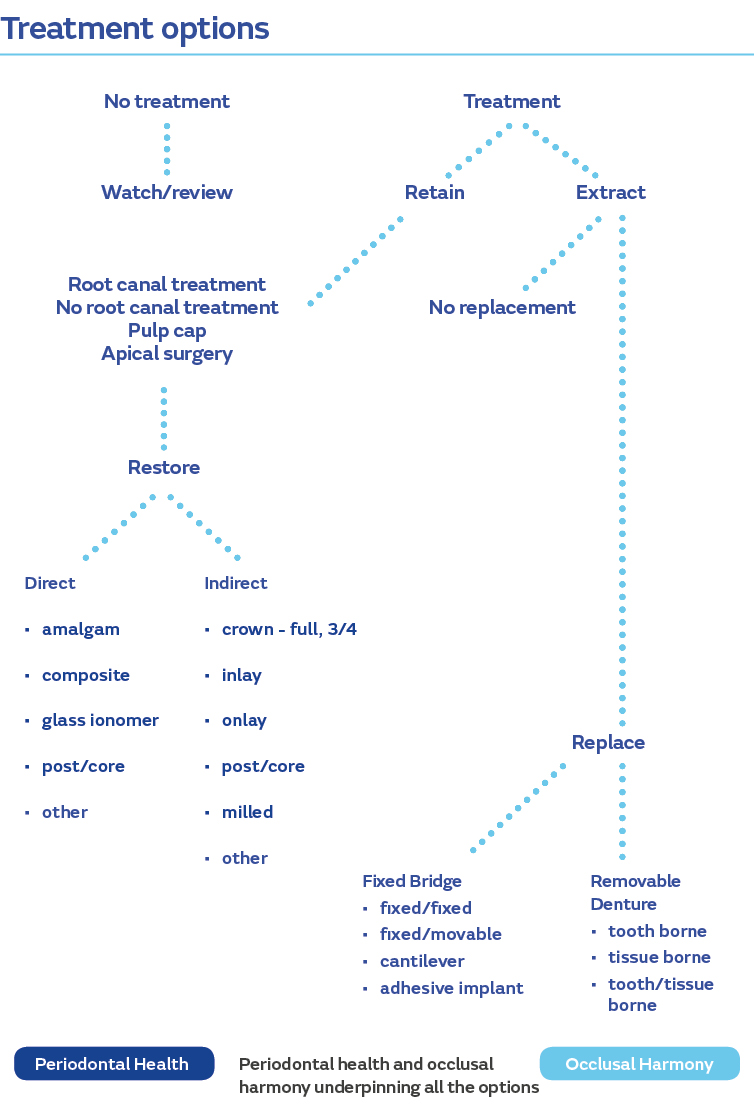

The important questions to ask here are: what am I doing and why am I doing this? Whose interests are being served? The following flowchart will help to determine the treatment options:

2

From this flowchart we can see two main options: no treatment or treatment.

Since the patient has requested an improvement, no treatment is not really an option, but she should be told that treatment is not required clinically, if that is indeed the case. Assuming that the patient wishes treatment, we have to look at the treatment options. Extraction would be an extreme choice and so should be discounted. The tooth is vital, so root canal treatment is not required, therefore moving on to the next level we can see that there are two main options here, direct restoration or indirect restoration.

Under direct restoration we can replace the filling with a tooth coloured filling material or cover the whole of the front surface of the tooth with a direct veneer in composite. Under indirect restoration, we can cover the front surface of the tooth with an indirect veneer or a crown, either of which can have a material of choice.

Now that we have established the options, which are you going to choose? How are you going to make this decision? Rather than do this on a subjective basis (gut feeling), we can try to introduce a degree of objectivity into the equation. It will, of course, depend on what the patient wants. We know she wants the appearance of the UR1 to be improved because the filling doesn’t look nice. So, we have to establish what outcome we, together with the patient, should aim for. This can be either making the filling look better and accepting the other ‘faults’ in the tooth, or attempting to make the tooth, in its entirety, look nice both on its own and in relation to its adjacent teeth. The two will require different solutions.

There are modifying factors that affect the treatment options and the decision outcome, and it is important to take these into account for each of the possible options that we have selected above.

3 For each of these options here are some points to consider:

Occlusal Is there evidence of clenching or grinding? How much force will there be on the restored tooth? Is it necessary to alter the occlusion?

Tooth/restorationHow much more tooth tissue will be lost in restoring the tooth? Is an impression required? Is a temporary required?

PeriodontalIs the tooth mobile? Is there pocketing around the tooth? Is there plaque associated with the tooth?

Pulp/root canalIs a root treatment required? Is there a risk of pulpal damage/exposure? What is the status of the periapical tissues?

PatientWhat does the patient want? Cost? Time/visits/impressions?

DentistAppropriate skill level? Appropriate experience? Adequate chairside support?

How these impact on each of the options will either be a benefit or a risk and can be weighted according to how much the patient or the dentist considers the impact to be on a scale of 1-5. A risk is given a negative rating and a benefit a positive rating.

We can consider the options as follows:

I realise that the allocation of weighting is subjective and will vary from dentist to dentist, as will the questions to be considered in each of the modifying factors. However, from the above, with a degree of objectivity, we can say that a direct composite veneer will be the best option to meet the patient’s requirements.

All of the above can be discussed with the patient and s/he can then make a more informed decision about the treatment and the cost, and then sign a document confirming that s/he has been informed of the options, the risks and the benefits of each and the costs, and that the patient has opted for treatment x.

There is no doubt that good judgment comes from experience and a lot of experience comes from bad judgment. We need to be reflective practitioners to reflect and learn and so improve our clinical decisions, thereby reducing the risk element of our work.

References

1. Bader JD, Sugars DA, Understanding Dentists’ Restorative Treatment Decisions, J of Public Health Dentistry 1992; 252: 102-110.

2. Caplin RL, Grey Areas In Restorative Dentistry - Don’t Believe Everything You Think 2015; p. 19 J and R Publishing.

3. Ibid, p. 49.